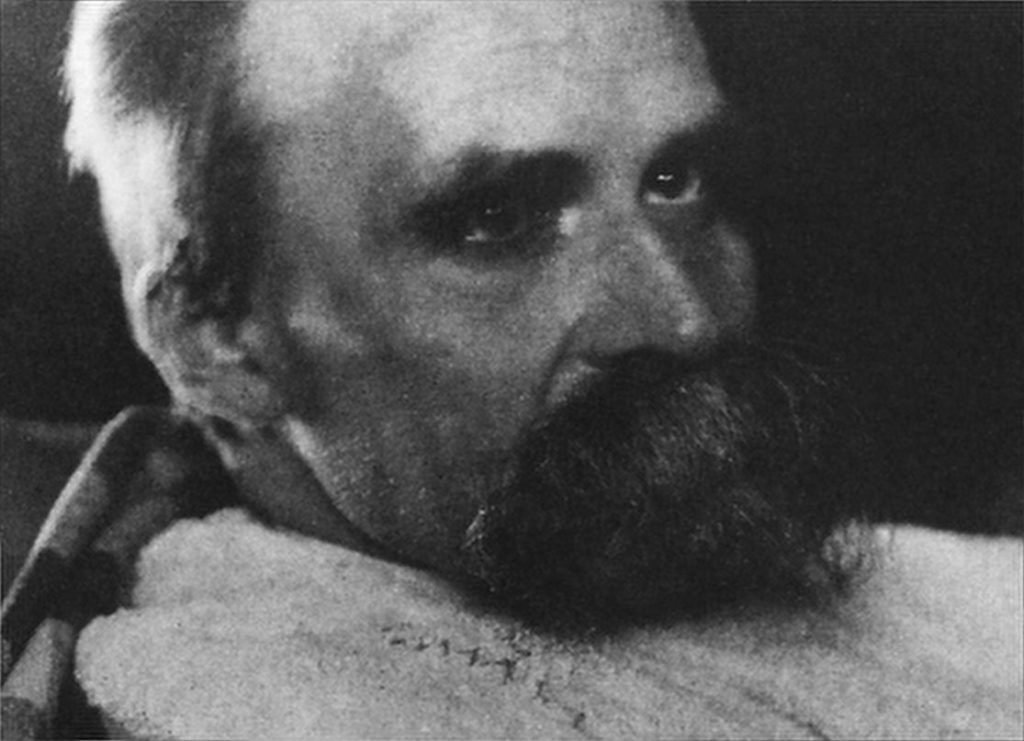

In this article I will explore the way Nietzsche has been taken up in neoconservative thought by looking at the work of Francis Fukuyama and his teacher Leo Strauss. Fukuyama interprets Nietzsche’s social theory that culminates in the idea of the last man as a theory of the decline of thymos in the modern world. This appropriation of Nietzsche opens interesting perspectives on contemporary phenomena, even if, as I will argue in my first section, it involves only a partial understanding of the concerns Nietzsche was addressing.

One of the most lively fields in recent Nietzsche scholarship has been the theme of Nietzsche and politics. Within this field, the appropriation of Nietzsche by the political Left has been especially prominent. Authors in the field of radical democracy have shown how Nietzsche’s philosophy can serve as inspiration for their project. One theme these authors discuss is Nietzsche’s critique of traditional concepts and rigidities in society, and it is precisely this that distanced thinkers on the political Right from Nietzsche. This can be seen from the ambiguous attitude toward Nietzsche in the work of conservative intellectuals. Allan Bloom, for instance, argues that Nietzsche saw the crisis of modernity but contributed to it himself by declaring the concepts of morality to be human projections with no objective basis in nature.

However, mostly in the United States, a field of research has emerged in which the political Right is appropriating Nietzsche. Within this field, Leo Strauss was among the first to take up Nietzsche. In the following I will focus particularly on Strauss’s student Francis Fukuyama and his recent confrontation with Nietzsche within the neoconservative tradition.

The term neoconservative is of relatively recent date, and Strauss has never described himself as such. The label was developed by followers of his work. Fukuyama draws support from neoconservative predecessors such as Irving Kristol, Norman Podhoretz, and Nathan Glazer. As we shall see, a theme that ties Fukuyama to them is his emphasis on the importance of traditional culture in modern societies.

Another central tenet of neoconservatism that Fukuyama adheres to is a skepticism concerning state intervention. In his most recent book, America at the Crossroads: Democracy, Power, and the Neoconservative Legacy, Fukuyama distances himself from the “practical” neoconservatives of the Bush administration. In chapter 1, he identifies four common principles of neoconservatism he adheres to: (1) a concern with democracy, human rights, and the internal politics of states (in contrast with “realist” international relations); (2) a belief that U.S. power can be used for moral purposes; (3) skepticism about the capacities of international law and institutions; and (4) the concern that ambitious social engineering often leads to unexpected consequences, undermining its own ends.

Hence, in contrast with classical realists like Henry Kissinger and in agreement with the ideologists of the Bush administration, Fukuyama does believe that the United States could and should use its power against human rights abuses abroad. However, he differs from the Bush administration on its approach to Iraq. A critical flaw there has been the belief in the possibility of establishing a working democracy ex nihilo. This contradicts the fourth principle of what Fukuyama believes to be the neoconservative legacy. In his earlier book State Building, this principle was one of the central arguments.

In this article I will explore the way Nietzsche has been taken up in neoconservative thought by looking at the work of Francis Fukuyama and his teacher Leo Strauss. Fukuyama interprets Nietzsche’s social theory that culminates in the idea of the last man as a theory of the decline of thymos in the modern world. This appropriation of Nietzsche opens interesting perspectives on contemporary phenomena, even if, as I will argue in my first section, it involves only a partial understanding of the concerns Nietzsche was addressing.

I argue that a line of reasoning in Nietzsche’s late philosophy, the project of grosse Politik, can be understood as a response to this development. In subsequent sections, I examine the way neoconservative thought has responded to this idea of the decline of thymos. Strauss agrees with Nietzsche’s diagnosis but does not follow him in his project of grosse Politik, leading him to a skeptical position on the possibility for human flourishing in the modern age.

Fukuyama, on the other hand, takes issue with the depiction of the modern world as the preeminence of the last man. In three different lines of argumentation, Fukuyama contends that an eclipse of thymos is not the necessary outcome of modernity. If grosse Politik is Nietzsche’s answer to the eclipse of thymos, yet grosse Politik is not something we wish to endorse, Fukuyama’s reply to the idea of the…